| Pennwood "Numechron" Clocks | ||

|

|

||

|

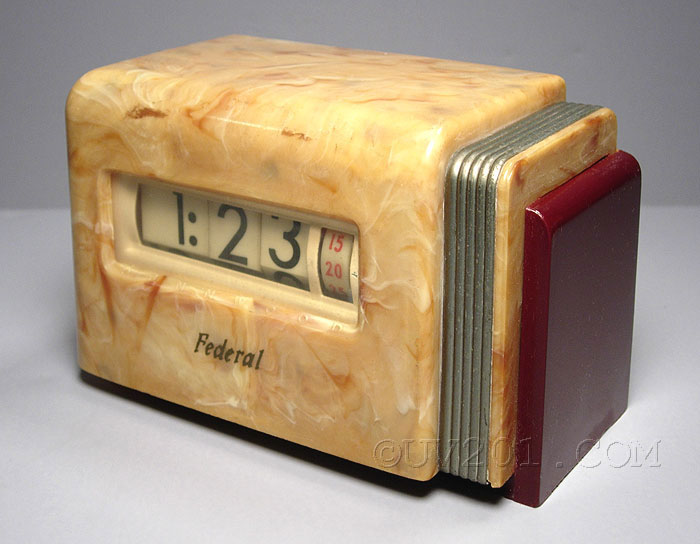

The Pennwood Electric Company was founded in the early 1930's, and was one of the first to market a digital clock. They were located in Pittsburgh, PA, at any of several addresses. They also manufactured industrial timers, and other electric devices. At some point, the company name was changed to the "Pennwood-Numechron Company". Pennwood stayed in business until 1972, when the company was sold to the Spartus Corporation, which continued making these clocks for several more years. The Pennwood movement appears to have found it's way into several radios, one of which is the 1940 Hamilton-Ross "Telatime". The earliest may be the 1934 high-end console made by Colonial for Sears-Roebuck, the model 1722. Pennwood movements were also used in clocks made by Lawson, Barr, General Electric, and others. The first clock shown here is the "Swank" model from 1948. The case is marbleized Tenite plastic and the base is die-cast metal, with a gold tinted lacquer finish. It is marked with the Federal name on the front, which may have been a store name, but it is marked Pennwood on the bottom. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

This is the Pennwood "Moderne" model of 1948 and, like the one above, it also bore the "Federal" name. |

||

|

||

|

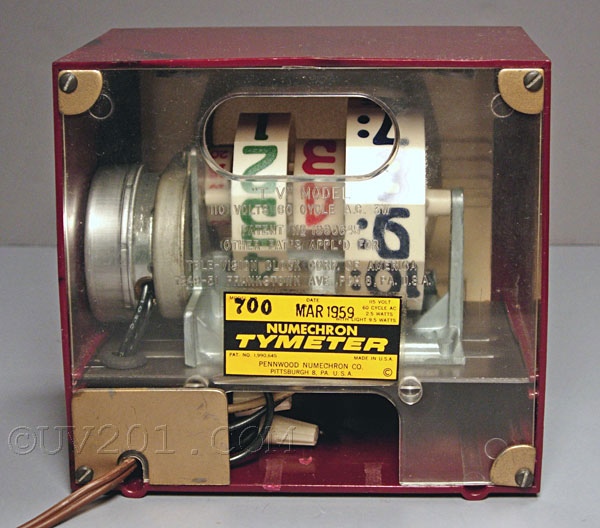

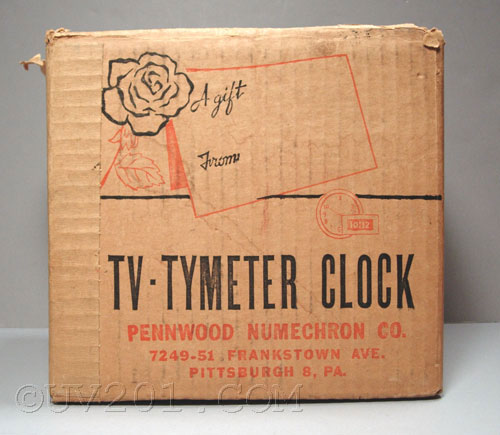

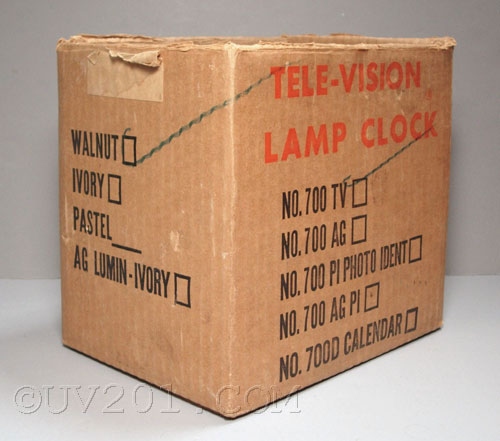

The most often seen Pennwood clock is this 1950's model 700 "TV Tymeter" lamp-clock. Many of the early TV's did not have especially bright pictures, so viewing was done in a darkened room. To alleviate eyestrain, lamps were used to provide some dim, shadowy lighting around the TV. Most of these were cheap porcelain figural lamps and, for some unexplained reason, the most popular style consisted of a black panther prowling through a jungle scene. Grotesque planter/lamps, with their legacy of white rings and ruined veneer, were also popular. This clock was a more practical approach to the problem. Pennwood advertised it as a "Glolite Colorama Television Lamp-Clock with Focalizer Stare-Break". Whew! Interestingly, the clock is marked both with the Pennwood and "Television Clock Corp. of America" names. A standard 7 1/2 watt nightlight bulb provided the illumination, controlled by the switch in the front. The clear Lucite back allowed the the light to project to the rear. |

||

|

||

| Why didn't all manufacturers put dates on their products? | ||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| The red clock shown above

was actually designed to be hung on a wall. The case was made of

Tenite plastic which was a particularly troublesome material, being

subject to warpage, cracking, and, in extreme cases, complete

disintegration. It was also available in white. This clock

was available at least as early as 1941, and production apparently

resumed after the war, as this example was made in 1946.

The white clock shown below was a desk clock whose design strongly resembled the Philco model 42-350 radio. This clock was known as the model 300 "Topper", and was made in 1948. It was also available in a marbleized brown color. This example shows the considerable amount of the warpage that is typical of Tenite. |

||

|

||

|

||

| Shown above and below is the Numechron "Imperial" clock, made circa 1948. Similar models were made before the war. The streamline design is very typical of the 30's, though by the late 40's, it was somewhat dated. The brown Bakelite case was accented by three Tenite plastic fins though, unfortunately, one is missing on this example. These fins are extremely fragile, and it normal to find these clocks with no fins at all. The prewar versions used clear Lucite fins. | ||

|

||

|

||

|

This stunning red and white Pennwood surfaced on eBay (no, I didn't buy it). The pictures appear here courtesy of the seller. It is made of white Plaskon with red Tenite fins. The decal on the bottom shows it as a model 600. It was made in 1955, so clocks of this general design were made for at least 15 years. |

||

|

||

|

||

| Pennwood Model 6C Circa 1940 | ||

|

||

| Pennwood "Zephyr" 1939 | ||

|

|

|

|

||

|

This clock was produced in 1953 by the National Cash

Register company as an award or a retirement gift for an employee.

It used the standard Pennwood movement. The two drawers are

functional and could be used for storing stamps, paper clips, or other

small items. In fact, they must be removed to gain access to the

number wheels so that the clock can be set. The clock is heavy for it's size, weighing just under 5 pounds, and it stands about 7 inches high. This clock was very well made, and definitely not a mass-produced item. The case was fabricated from sheet steel that was stamped, then welded or riveted together. The drawers and bottom section were produced as a unit, and the pieces numbered to keep them together. Each of the buttons were cut from plastic rod stock and individually glued into place. The numbers on them were hand drawn, though that may have been done later. The cost of producing clocks like this must have been significant, so they probably went only to executives, or very productive salesmen. They were not sold to the public, and are quite rare. |

||

|

||

| Home | ||